Outlier Health

Long drop: How many SA schools still lack proper toilets?

📝 By Laura Grant

At the end of last year, the new Minister of Basic Education Siviwe Gwarube said her department would eradicate all remaining ‘identified’ pit toilets in schools across the country by 31 March 2025. This was her world toilet day promise (yes, world toilet day is a thing).

How close are we to meeting the 31 March 2025 deadline to eradicate pit toilets?

That’s hard to say because it depends on where you look for information.

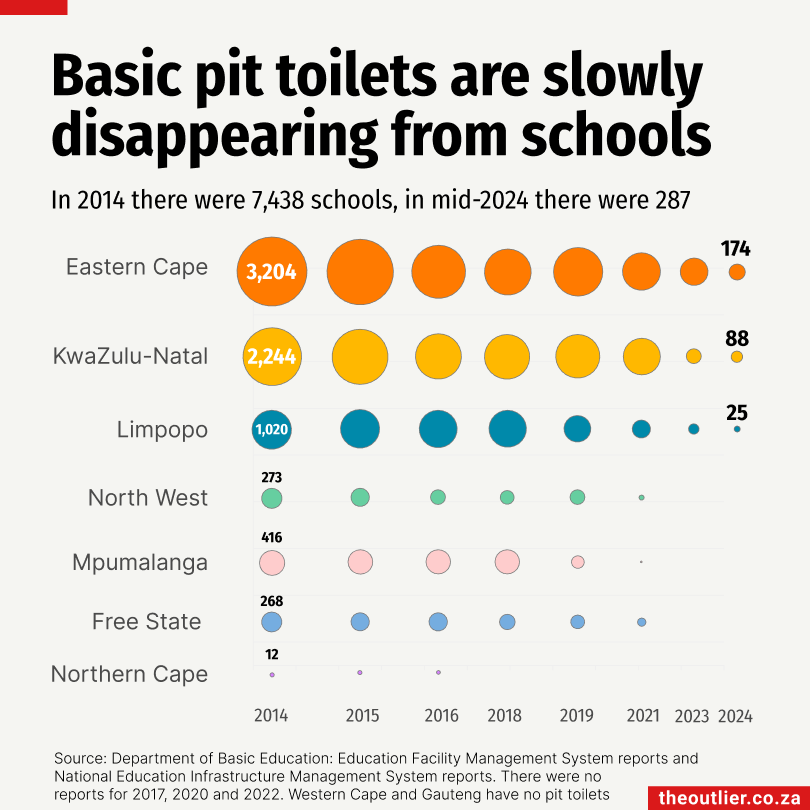

Let’s start with the Education Facility Management System (EFMS), which is where the Department of Basic Education (DBE) captures information about school infrastructure. It used to be called the National Education Information Management System (Neims). The latest EFMS report, dated 3 June 2024, shows 287 schools in South Africa with basic pit latrines as their only toilets. That’s a big drop from the 7,438 schools dependent on basic pit toilets in the 2014 Neims report.

A back-of-the-envelope calculation shows that over the past 10 years pit toilets have been replaced with appropriate toilets at an average rate of 715 schools a year – or about two schools a day. When you look at it that way, you don’t really get a sense of urgency.

Nevertheless, by 2024 pit toilets were eradicated from schools in all but three provinces, according to the Education Facility Management System data. At the cracking pace of two a day, it should have taken about five months to finish the last 287 schools.

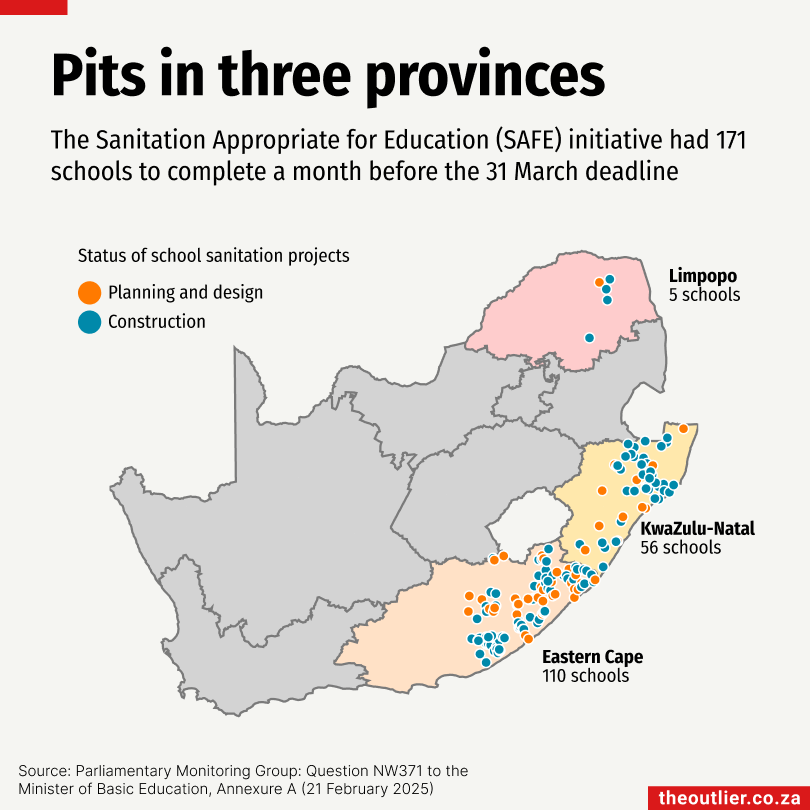

The most recent data we can find, dated 17 February 2025, in a response to a question in parliament, is a list of 171 schools where work was still underway at the beginning of the year. Work at all those schools was expected to be finished by the 31 March deadline, the Department of Basic Education said.

The map below shows where those 171 schools are: five in Limpopo, 56 in KwaZulu-Natal and 110 in the Eastern Cape.

These 171 schools are very likely not all the schools in the country that are reliant on basic pit toilets. They are the ones that fall under the Sanitation Appropriate for Education (SAFE) Initiative.

The initiative was launched in 2018, five months after five-year-old Lumka Mkhethwa, fell into a pit toilet at her school in Bizana, Eastern Cape, and died. We created a data story about this at the time.

The SAFE initiative was meant to speed up the delivery of appropriate sanitation to schools that were dependent on basic pit toilets. At the time there were 1,598 such schools in the Eastern Cape.

Across the country, SAFE had 3,375 schools on its books and by February 2025, the Department of Basic Education said 3,204 of them had received sparkly new toilets. Siviwe Gwarube has been proudly stating that work at 93% of the schools with pit toilets is complete, based on these numbers.

There are many who doubt that the 31 March deadline will be met, even for the schools on the SAFE initiative list. It’s also doubtful whether what is on the SAFE list is a complete list of all the schools that rely on pit toilets in the country.

How reliable are the numbers?

Let’s use Limpopo as an example.

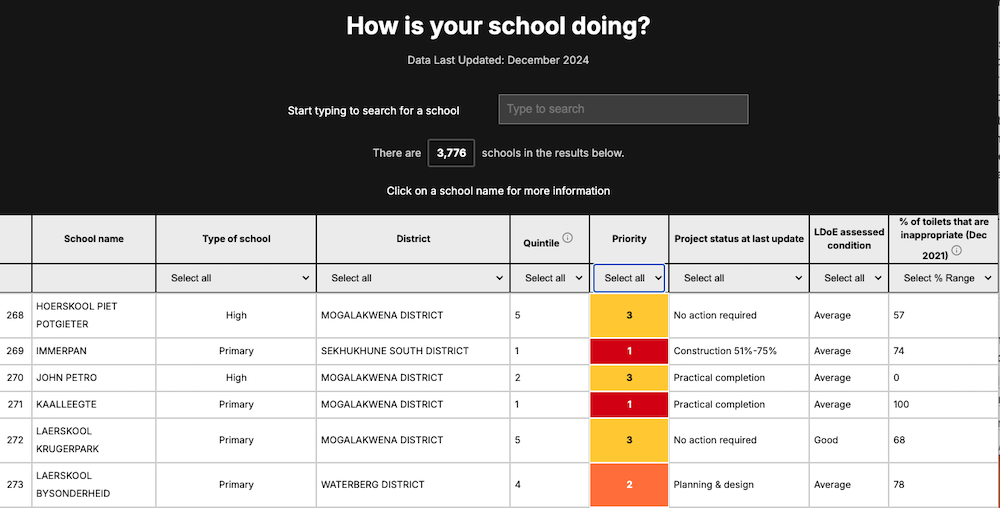

SECTION27 has been monitoring the Limpopo Department of Education’s (LDoE’s) progress in eradicating pit toilets and fixing other sanitation problems at schools in the province since December 2021.

Every six months since December 2021, the Limpopo education department reports to the High Court in Polokwane on the progr ess being made to fix the sanitation in schools because of a court order handed down in the Michael Komape case. Michael died after falling into a pit toilet at his school in Limpopo in 2014. He was five years old.

On behalf of SECTION27 we’ve turned these batches of updates (they’re scans of PDFs of spreadsheets) back into spreadsheets (there have been six batches so far), put them in a database and built a searchable table and a map that allows anyone to search for a school, see what its sanitation facilities were in 2021 and follow its progress over the past three years. It’s named the Michael Komape Sanitation Progress Monitor to honour the child who died.

The Limpopo education department divided the province’s schools into three categories based on the state of their sanitation, after conducting an audit. Priority 1 schools had inappropriate sanitation, ie. they had pit toilets only and needed the most urgent attention. Priority 2 schools had inadequate sanitation, eg, not enough appropriate toilets for the number of learners at the school and maybe some basic pit toilets, and Priority 3 schools, which had compliant sanitation but in need of refurbishment and maybe also some pit toilets that needed to be removed.

The Priority 1 schools need to be fixed by 31 March 2025

If the data made available about Limpopo’s schools is an indicator of the data available for other provinces, then the minister has her work cut out for her in fulfilling her promise to eradicate the pit toilets in all schools.

More than 500 Limpopo schools changed priority category over the three-year period. Twenty-six of the original Priority 1 schools were moved to another priority and nearly 250 schools were moved into Priority 1 from the other two priority categories. As a result, keeping track of the schools that have pit toilets only in Limpopo is not as easy as you’d think.

Then there are the schools that have been listed as ‘to be closed’. There are close to 90 of them and some appear to be in a kind of limbo where nothing is being done to improve their sanitation. It’s hard to tell from the information being provided by the Limpopo Department of Education. Some of them have been listed as ‘to be closed’ for three years.

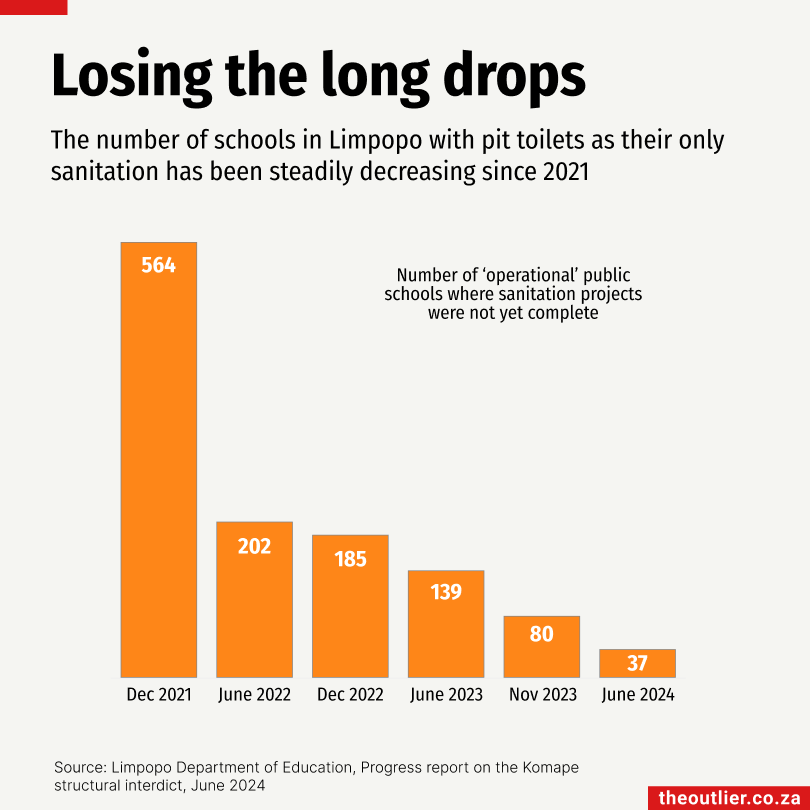

According to the Limpopo Education Department’s latest progress report, which comes in the form of a slide deck, upgrades had been completed at 527 of the 564 Priority 1 schools in the province by June 2024. Only 37 schools remained and they were all expected to be finished by the deadline.

It’s worth noting that the numbers in the department’s slide decks don’t always tally with the data we extract from the other documents submitted, and in 2021 there were originally ~360 Priority 1 schools, not 564. But, at least progress is being made.

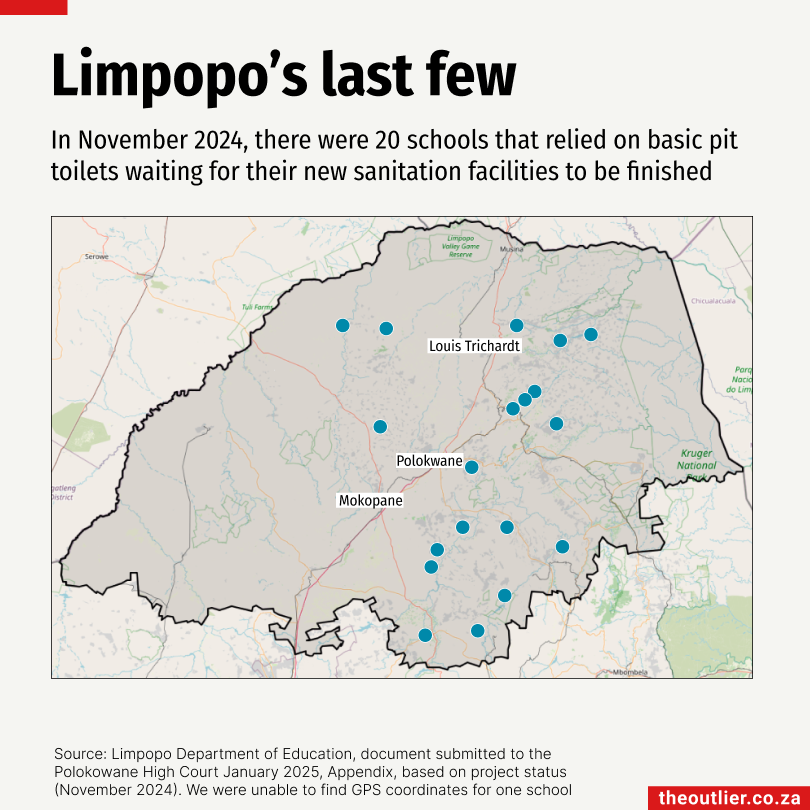

What we did find in the most recent batch of documents is a progress update for November 2024 in which there are 20 Priority 1 schools at which work is still in progress (see map below). There is an interactive version of this map on the Michael Komape Sanitation Progress Monitor that shows all the schools we can find GPS coordinates for.

SECTION27 is sceptical about the LDoE meeting the 31 March deadline for the Priority 1 schools. This is not the first deadline the province has missed.

It has done site visits to schools with ‘urgent sanitation needs and immediate safety risks’ where the court order mandated the LDoE to provide mobile toilets while the schools’ permanent toilets are being built.

On a site visit to a school last month, SECTION27 found that 1,000 learners were sharing eight mobile toilets. They become full very quickly and ‘within days, these toilets are maggot-infested, with an unbearable stench and are only cleaned once a week during school hours.’ The construction of the school’s new permanent toilets had not even started, SECTION27 reported.

At another school, four mobile toilets service over 570 learners. ‘As many learners must queue during break time, some accidentally relieve themselves while waiting and must be sent home,’ SECTION27 reports.

Thanks to the Komape case court order, people are able to see what the sanitation status of each of the schools in Limpopo is reported to be by the LDoE. This level of information is almost impossible to find for the other provinces.

SECTION27 commissioned us to build the sanitation monitor to allow the public to access the available information and compare it to their lived experience, to help hold authorities accountable and ensure that unsafe and undignified sanitation is removed from our schools.

This is a case where good data could save a child’s life.

🦟 How climate change affects the spread of infectious diseases

For most of the December holidays, my home in Johannesburg has reeked of citronella oil in an attempt to ward off mosquitoes. Joburg is not a malaria area, so mosquitoes are just a nuisance. But imagine if that changed.

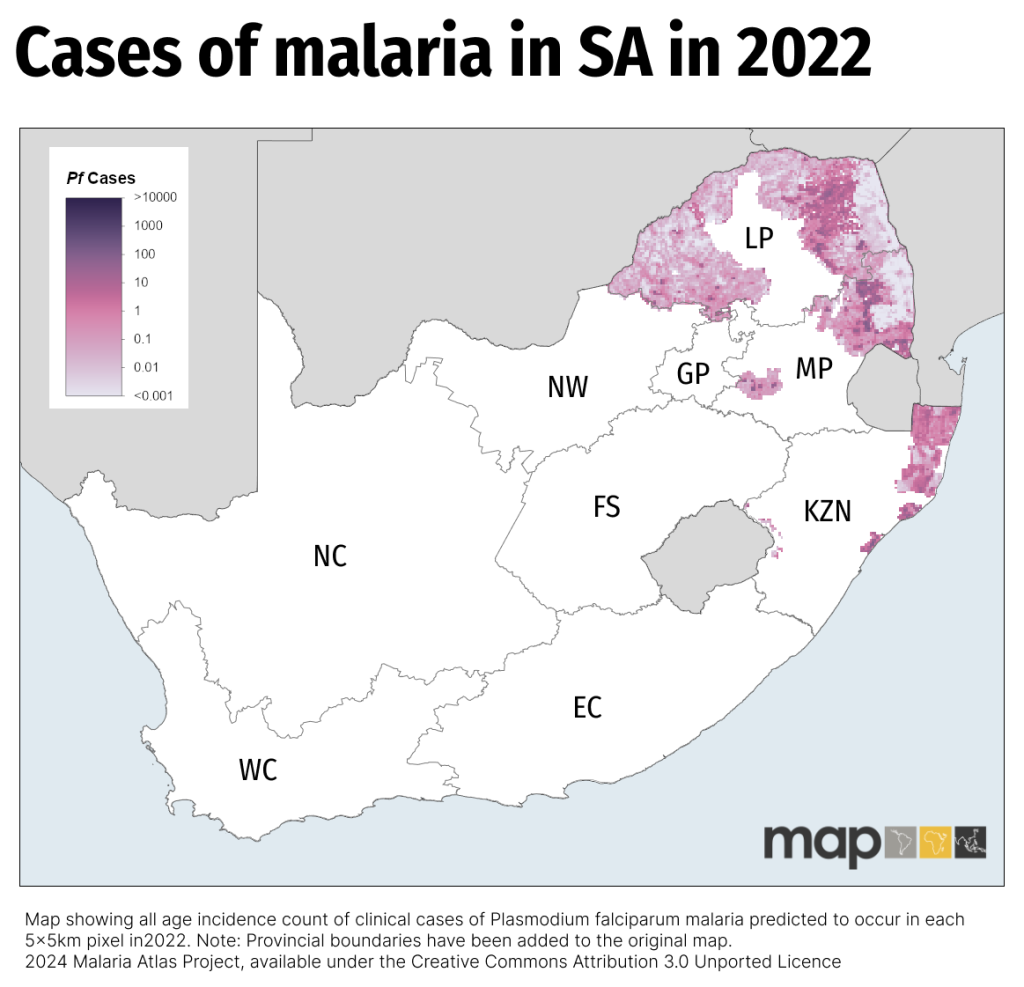

South Africa’s malaria areas are in Limpopo, KwaZulu-Natal and Mpumalanga near the borders with Zimbabwe and Mozambique. The map below from the Malaria Atlas Project showing malaria cases in 2022 in 5km x 5km blocks gives a good idea of where the malaria areas are.

South Africa aims to eradicate malaria by 2030. It appears to be making good progress as the number of reported cases have plunged from 64,622 in 2000 to 9,795 in 2023, according to Department of Health data.

But rising temperatures may make it harder to meet that target because temperature affects the growth cycle of the parasite that causes malaria (mostly Plasmodium falciparum in SA). At temperatures below 20°C it cannot complete its growth cycle in a mosquito, so malaria cannot spread. Areas higher than about 1,000m above sea level are also usually malaria free. Joburg is over 1,700m above sea level.

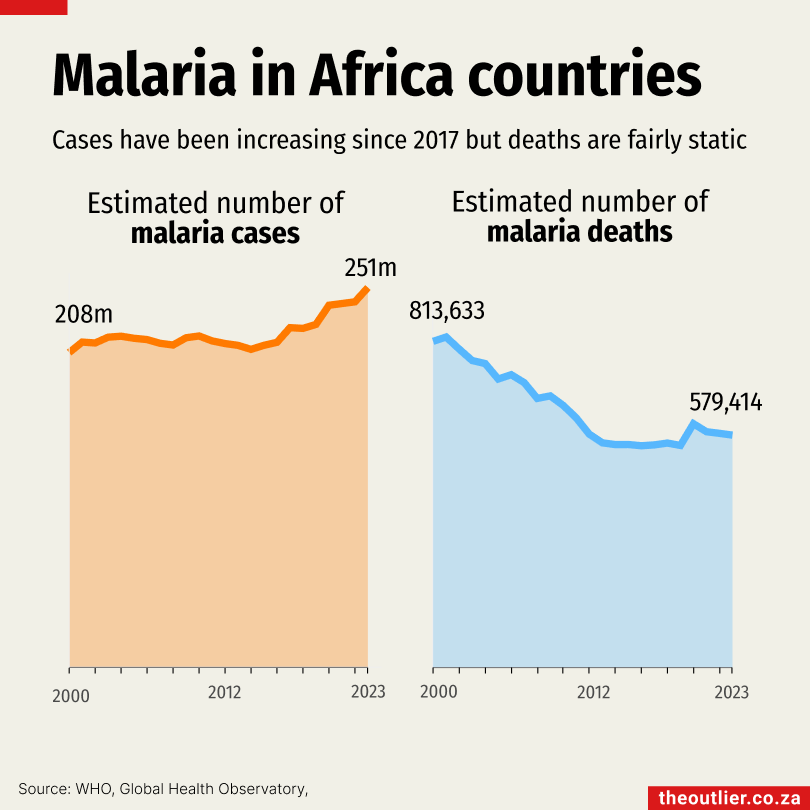

In many other African countries, thousands of people die every year from the disease. The Malaria Atlas Project, in a report entitled Climate Impacts on Malaria in Africa published in November 2024, predicts that thanks to climate change more people will die of malaria and notes that more investment is needed in the fight against the disease.

There’s an intricate interaction between climate change and infectious diseases, according to the scientists of the Climate Consortium who put together the Climate Change & Epidemics 2024 report released in November.

A side note: the report was edited by Tulio de Oliveira, the SA scientist who became a household name during Covid and who has been listed among the top 1% of highly cited researchers globally in 2024.

There are three main ways the interaction of climate change and disease plays out, according to the report.

Firstly, the ‘slow but relentless’ increase in temperature allows diseases such as malaria and dengue fever, which is also spread by mosquitoes, to appear in places that were previously unaffected.

Secondly, the increasing frequency of extreme weather events, such as floods.

Thirdly, changes in temperature and rainfall prompt people to migrate. If water becomes scarce and crops fail and people will be forced to move in search of food and economic opportunity.

Dengue fever

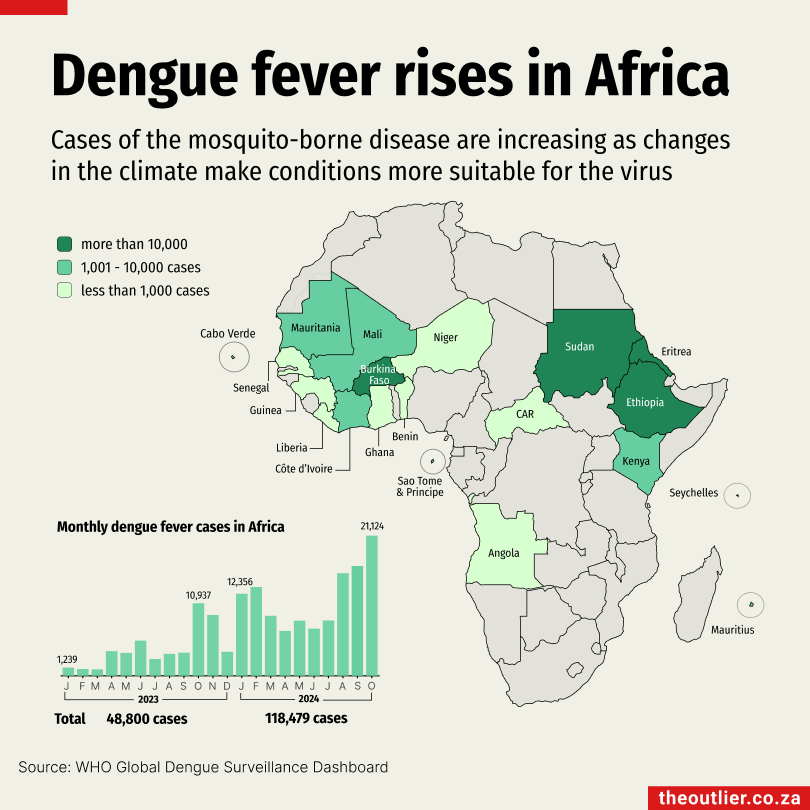

In 2024, the world’s largest epidemic of dengue fever was recorded. Although South American countries were hardest hit, dengue cases in African countries increased by 140%, from 48,800 in 2023 to over 118,000 by October 2024.

The map below shows where cases of dengue fever were reported in African countries in 2023 and 2024. Ethiopia had the misfortune of experiencing two dengue outbreaks in the past two years.

No dengue fever cases have been reported in South Africa but, says the National Institute of Communicable Diseases, the type of mosquito that carries dengue fever, Aedes aegypti, is present in certain regions, such as the KwaZulu-Natal coastline.

Floods, droughts and cholera

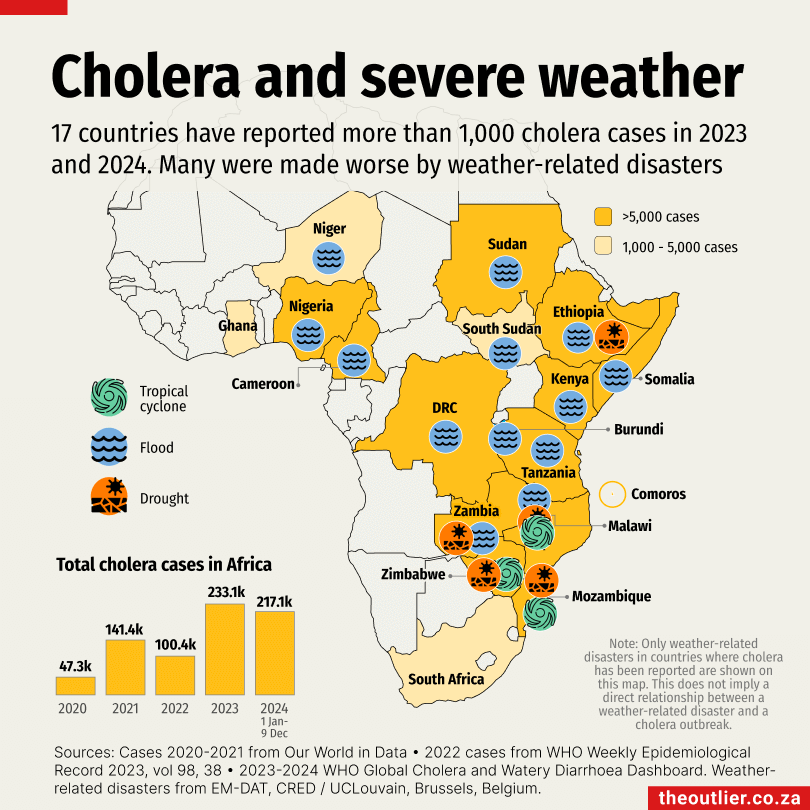

The increasing frequency of extreme or severe weather events, such as floods, cyclones, extreme temperatures and droughts damage infrastructure, contaminate drinking water sources and reduce access to clean water, creating an ideal environment for cholera to thrive.

Seventeen African countries reported more than 1,000 cases each of cholera in 2023 and 2024. Many of these cholera outbreaks were linked to or made worse by weather-related disasters. The map below shows those countries as well as weather-related disasters reported over the same period in the EM-DAT international disaster database.

Malawi, for example, experienced its biggest cholera outbreak ever thanks to flooding caused by two tropical cyclones in early 2022. Then in March 2023, Cyclone Freddy, hit. The cholera health emergency lasted from December 2022 until July 2024. In 2023 and 2024 alone more than 41,000 cases of cholera were recorded in Malawi by the WHO and more than 1,000 people died.

Cyclones and heavy rains also intensified a cholera outbreak in Mozambique, and epidemics in Zambia and Zimbabwe were exacerbated by both drought and floods.

South Africa’s cholera outbreak in 2023 was not weather-related, but started when an infected person travelled from Malawi to Gauteng. Similarly, an outbreak in the Comoros this year has been linked to a passenger who arrived on a boat in January.

Migration

Changing rainfall patterns such as severe drought can push people to migrate away from affected areas, as can conflict.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo conflict and floods has forced people to move to camps where conditions are crowded and access to clean water is limited. In Ethiopia, Sudan and Somalia, the internal displacement of people worsens cholera outbreaks.

In Sudan, conflict since April 2023 has caused the displacement of 10-million people. Here too floods have worsened the situation.

Poverty, malnutrition, poor sanitation, lack of access to clean drinking water and poor access to health care are exacerbated by changing climate patterns.

There is a need for infrastructure that can withstand extreme weather and ensure medical supplies during crises, states the Climate Change and Epidemics Report. Countries need to build systems to ensure communities are able to adapt to changing conditions and are less vulnerable to disease outbreaks.

HIV in South Africa: Deaths drop by 80% as treatment uptake grows

An estimated 7.8-million people are living with HIV in South Africa and three-quarters (5.9-million people) are on antiretroviral medicine.

with The Outlier

• Getting started with spreadsheets

• Learn pivot tables

• Data visualisation tips

• Map-making with data.

Cholera surges in Africa: Over 110,000 cases in 5 months

More than 110,000 cases of cholera were reported in Africa in the first five months of the year. This is half of the total reported in 2023 and more than all the cases in 2022.

Last year, a cholera outbreak in South Africa claimed the lives of 47 people. The disease spread quickly in areas with poor sanitation and limited access to clean water.

Globally, cholera remains a significant threat. In January 2023, the World Health Organization classified the global cholera outbreak as an acute grade 3 emergency after 27 countries had reported cholera, some of which hadn’t had a case of the disease in decades.

In many countries the fatality rate was well above the target of one death per 100 cases. The situation was not helped by a shortage of cholera vaccines.

Cholera outbreaks highlight the need for Africa to make its own vaccines

There is a worldwide shortage of cholera vaccines, and only one WHO-approved producer in the world, EuBiologics in South Korea.

In February 2024, Doctors Without Borders, a medical humanitarian organisation, reported that the global cholera vaccine stockpile had been exhausted. Already in October 2022 a decision was made to temporarily reduce the dosage of vaccine given from two to one as a way to stretch out the supply.

‘During the Covid-19 pandemic African countries were forced to the back of the queue for life-saving Covid-19 vaccines. It taught us that we need to have our own local manufacturing capacity,’ says vaccinologist Edina Amponsah-Dacosta.

In 2021, African leaders set a target to produce 60% of Africa’s vaccines in Africa by 2040. South African biopharmaceutical company Biovac is developing an oral cholera vaccine, which will start clinical trials in 2025.