Outlier Climate

Private power: RSA Renewable Energy in 6+1 charts

📝 By Gemma Ritchie and Laura Grant

South Africa needs a rapid switch to renewable energy. Not only is it critical to keep global temperature increase and its consequences in check, it would also be good for South Africa’s economy. This was a key message of a public lecture at Wits University this week by Sir David King, the head of the Climate Crisis Advisory Group and the former chief scientific advisor to the UK government.

King, who studied at Wits in the 1960s, urged South Africa to lead the global south in the transition away from fossil fuels in an inspiring talk entitled ‘The Paris Agreement at a Crossroad: Pathways to a Sustainable Future’.

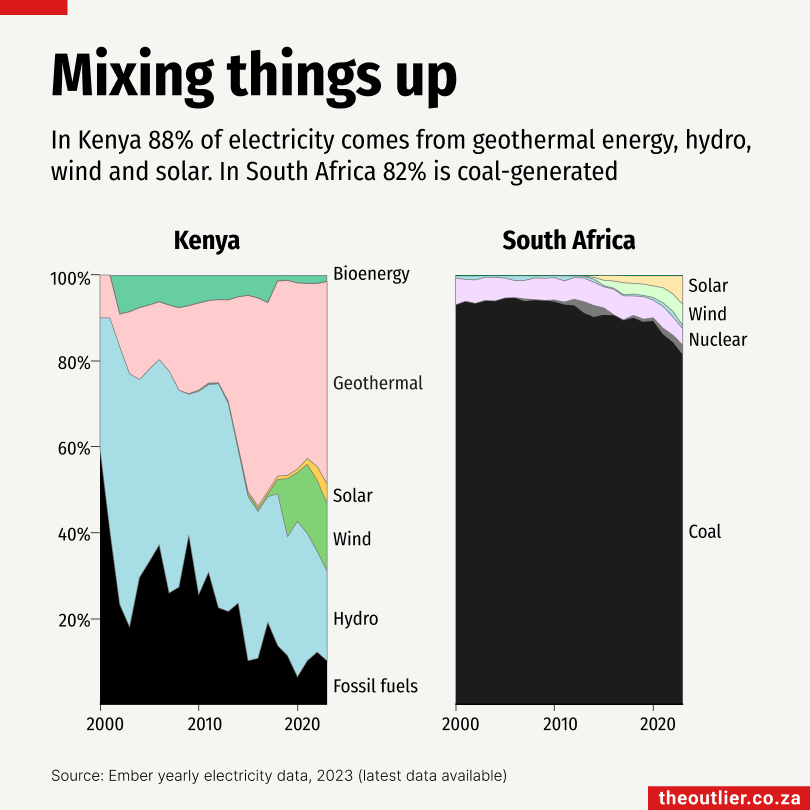

He held up Kenya, which generates nearly 90% of its electricity from non-fossil sources, as an example of what’s possible in Africa. South Africa is still heavily dependent on coal, but renewable energy’s share of the mix is increasing.

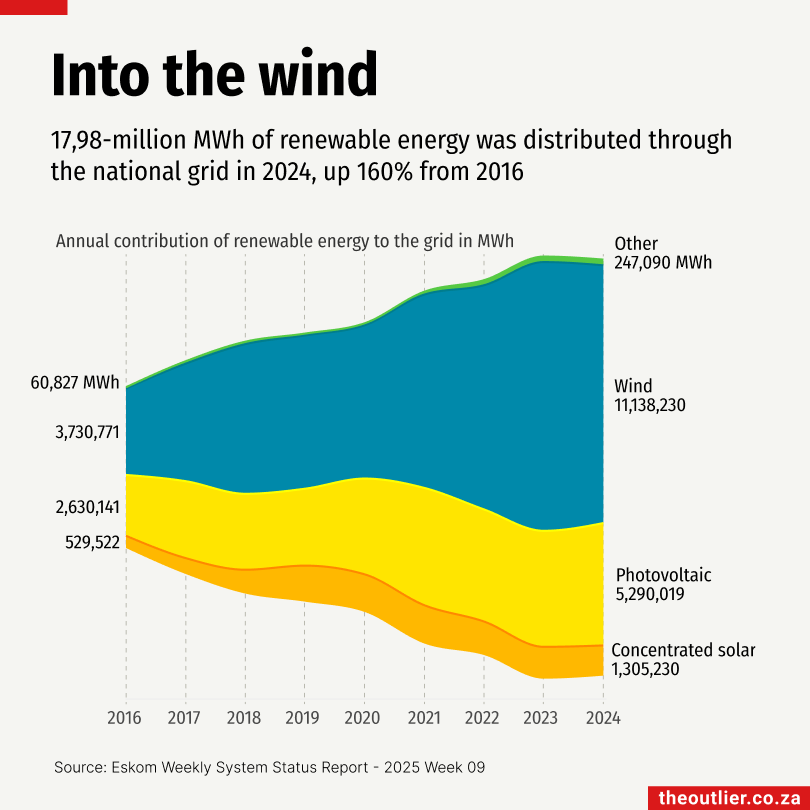

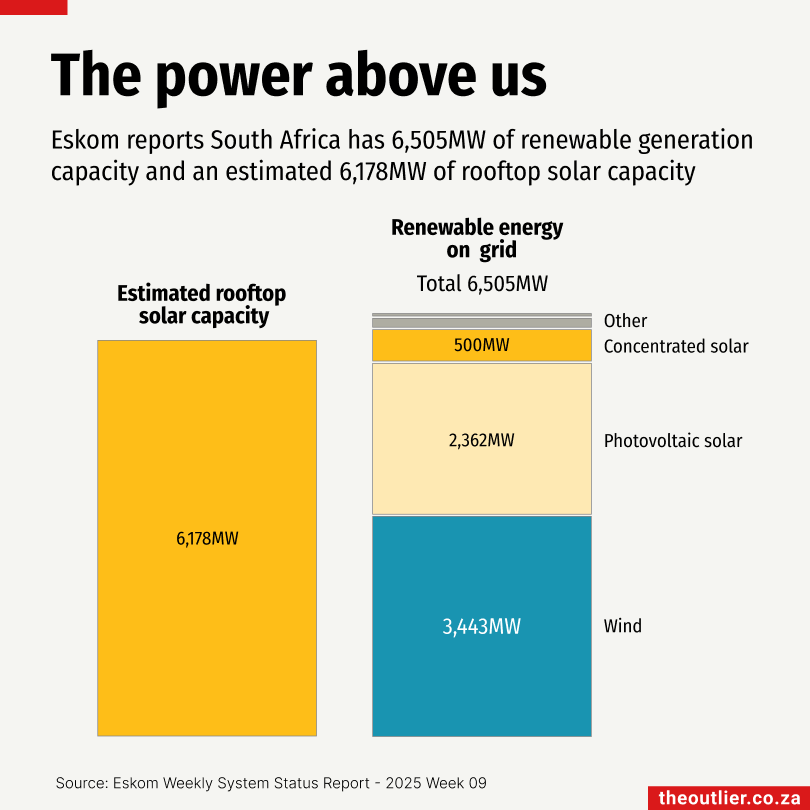

South Africa has 6,505MW of installed renewable energy capacity that generates power for the national electricity grid, according to Eskom. 53% is wind and 44% is solar. Just under 18-million megawatt-hours of electricity from renewables was generated in 2024, nearly two-thirds of it wind, the utility reports. One megawatt hour of electricity can power between 500 and 1,000 homes for an hour. There’s a long way to go before renewables can replace coal. But it’s a start.

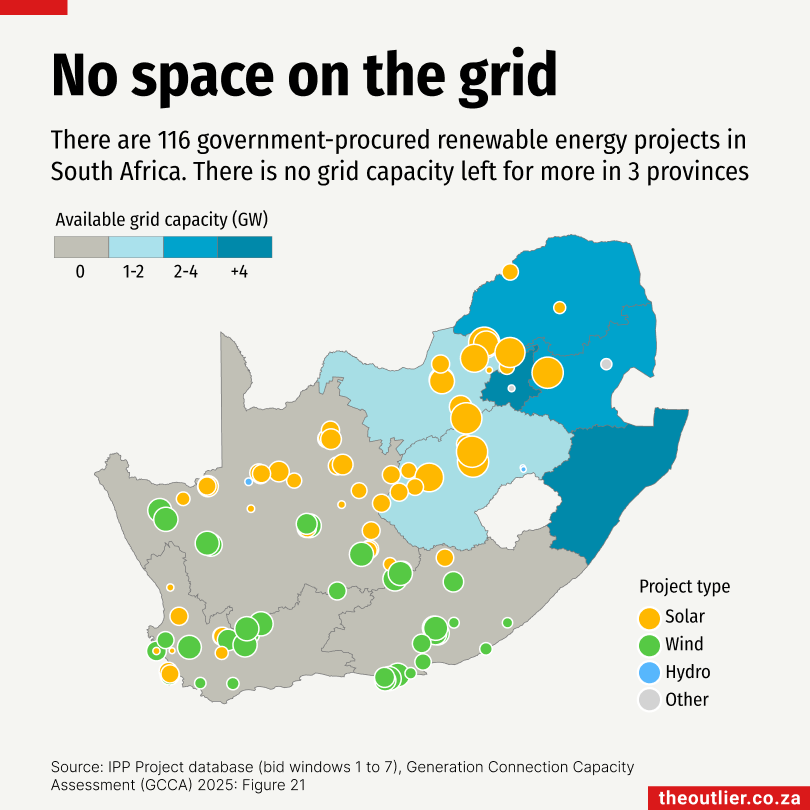

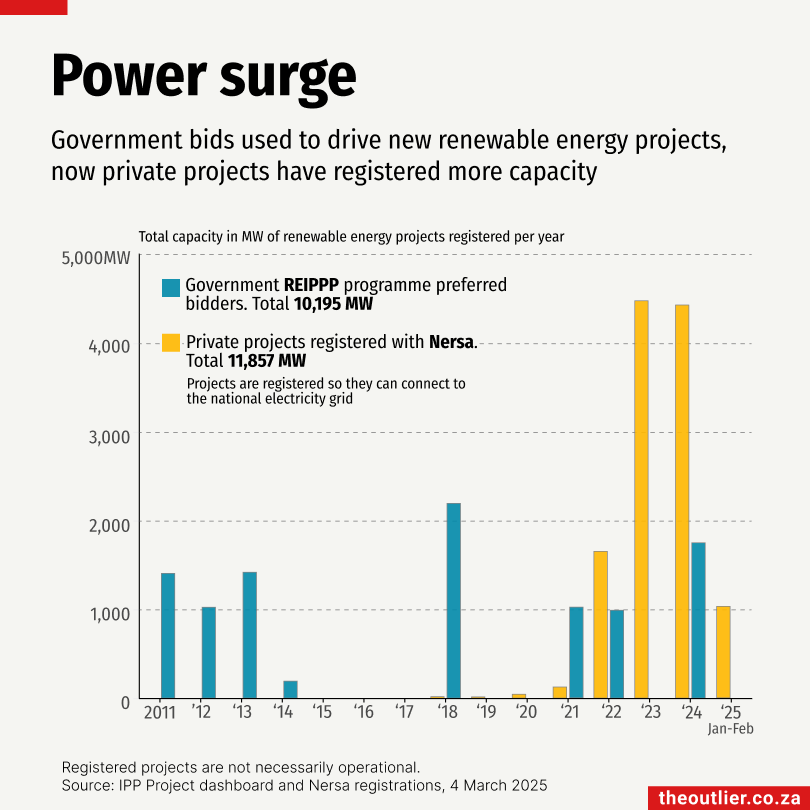

A key driver of the increase in renewable capacity is the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (REIPPPP). Launched in 2011, it was designed to facilitate private sector investment in renewable energy projects that connect to the national grid through a competitive tender process. Since its inception, 116 projects have been approved, in seven bid windows. Ninety-one of these projects are operational.

Forty REIPPPP projects are wind farms. Although there are more solar projects than wind projects, at present the wind farms are generating more electricity for the grid.

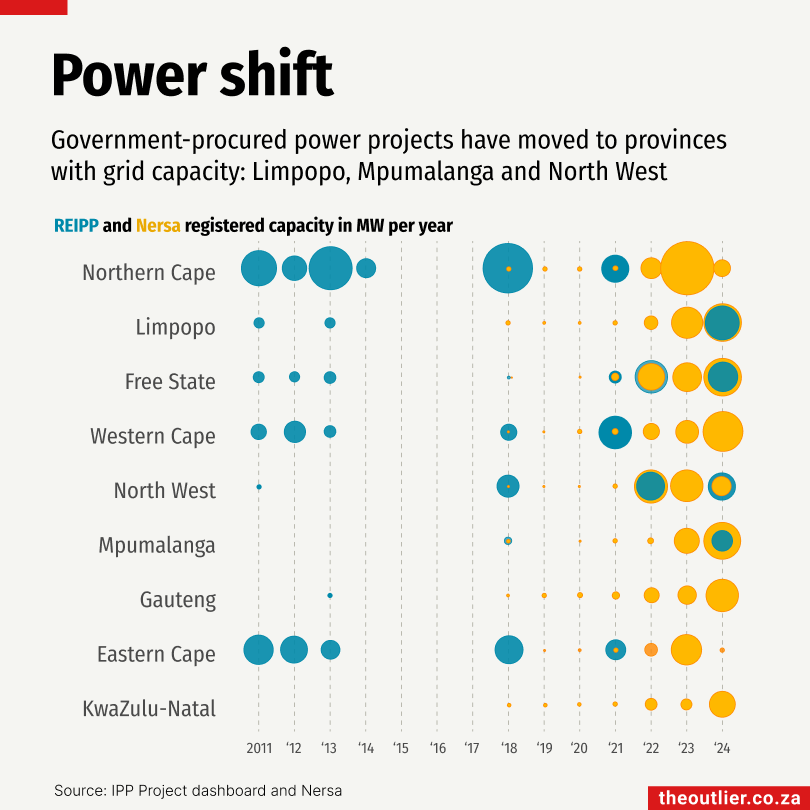

But there’s a problem. The areas that are rich in solar and wind resources – the Northern Cape, Eastern Cape and Western Cape – have run out of grid capacity, according to Eskom’s Generation Connection Capacity Assessment: 2025.

Thanks to years of loadshedding, private businesses and residents invested in rooftop solar and other energy alternatives, to compensate for the unreliable electricity supply.

By February 2025, the National Energy Regulator of South Africa (Nersa) had a list of registrations for private energy projects with a total installed capacity of 11,857MW – most of it solar. Nersa doesn’t provide information about whether these projects are operational.

It means that private companies have registered through Nersa more alternative energy capacity than the 10,195MW procured through the government’s REIPPP programme.

While the the Northern Cape and Eastern Cape are rich in solar and wind energy potential and are the site of many of the earlier REIPPPP projects, there’s been a big drop in registrations of both private and government projects because of the shortage of grid capacity. The bigger energy projects are now registered for Limpopo and the Free State, where there is space on the grid.

In the most recent REIPPP programme bid window, the successful bids were projects in the Free State, Limpopo, Mpumalanga and North West.

Eskom estimates that there is 6,178MW of private rooftop solar installed in South Africa. It’s almost as much as Eskom’s installed renewable capacity for 2025, according to the latest status report from Eskom’s National Transmission Company.

Rooftop solar systems, which aren’t connected to grid, are playing a part. They’re alleviating pressure on the national grid, said Eskom spokesperson Daphne Mokwena.

Billion-dollar blow

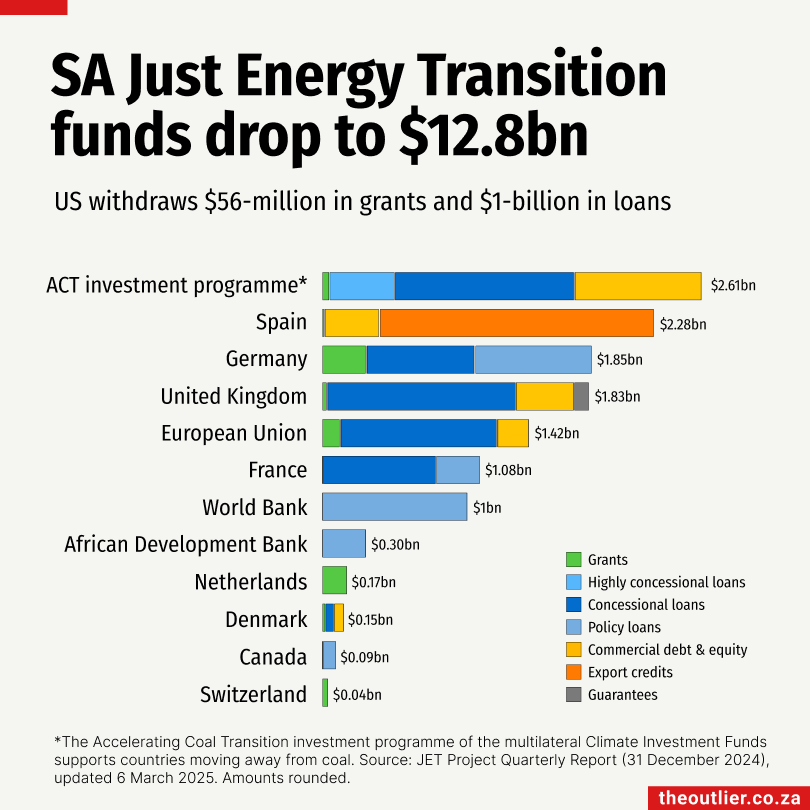

The United States has withdrawn all the funding it pledged towards the Just Energy Transition (JET), which amounts to more than $1-billion. The US has withdrawn from the International Partners Group, formed in 2021 with France, Germany, the UK, and the EU, to support South Africa’s efforts to decarbonise its economy. Even before this week’s announcement by the presidency, the US had already reduced the grant portion of it’s funding from $63-million to $56-million. The remainder of the funds were in the form of commercial debt and equity.

🦟 How climate change affects the spread of infectious diseases

For most of the December holidays, my home in Johannesburg has reeked of citronella oil in an attempt to ward off mosquitoes. Joburg is not a malaria area, so mosquitoes are just a nuisance. But imagine if that changed.

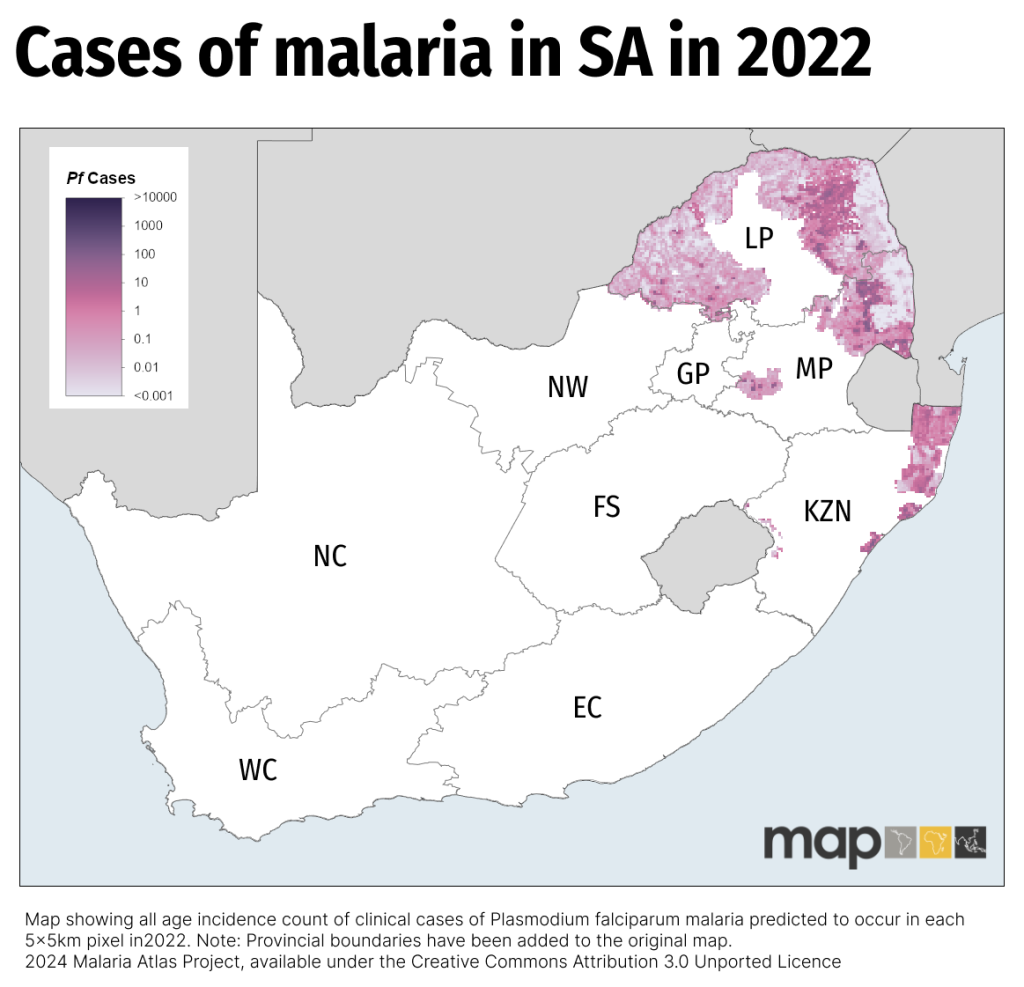

South Africa’s malaria areas are in Limpopo, KwaZulu-Natal and Mpumalanga near the borders with Zimbabwe and Mozambique. The map below from the Malaria Atlas Project showing malaria cases in 2022 in 5km x 5km blocks gives a good idea of where the malaria areas are.

South Africa aims to eradicate malaria by 2030. It appears to be making good progress as the number of reported cases have plunged from 64,622 in 2000 to 9,795 in 2023, according to Department of Health data.

But rising temperatures may make it harder to meet that target because temperature affects the growth cycle of the parasite that causes malaria (mostly Plasmodium falciparum in SA). At temperatures below 20°C it cannot complete its growth cycle in a mosquito, so malaria cannot spread. Areas higher than about 1,000m above sea level are also usually malaria free. Joburg is over 1,700m above sea level.

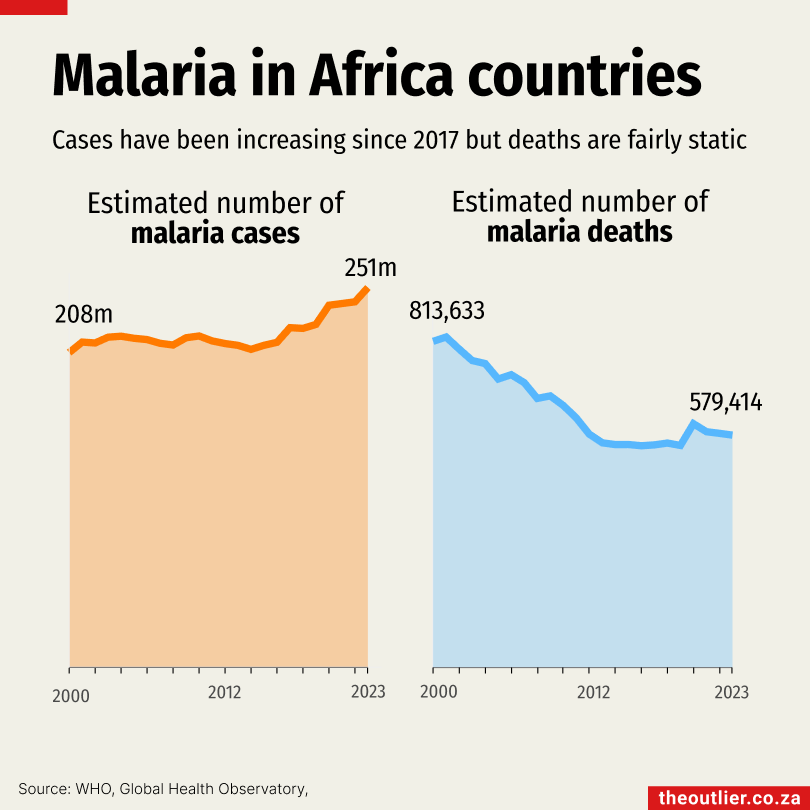

In many other African countries, thousands of people die every year from the disease. The Malaria Atlas Project, in a report entitled Climate Impacts on Malaria in Africa published in November 2024, predicts that thanks to climate change more people will die of malaria and notes that more investment is needed in the fight against the disease.

There’s an intricate interaction between climate change and infectious diseases, according to the scientists of the Climate Consortium who put together the Climate Change & Epidemics 2024 report released in November.

A side note: the report was edited by Tulio de Oliveira, the SA scientist who became a household name during Covid and who has been listed among the top 1% of highly cited researchers globally in 2024.

There are three main ways the interaction of climate change and disease plays out, according to the report.

Firstly, the ‘slow but relentless’ increase in temperature allows diseases such as malaria and dengue fever, which is also spread by mosquitoes, to appear in places that were previously unaffected.

Secondly, the increasing frequency of extreme weather events, such as floods.

Thirdly, changes in temperature and rainfall prompt people to migrate. If water becomes scarce and crops fail and people will be forced to move in search of food and economic opportunity.

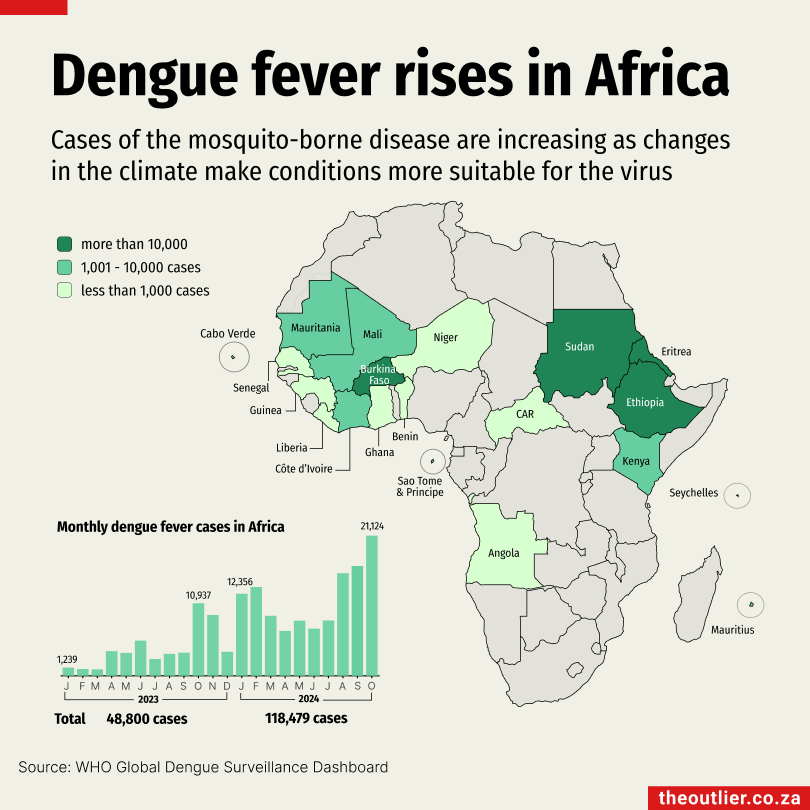

Dengue fever

In 2024, the world’s largest epidemic of dengue fever was recorded. Although South American countries were hardest hit, dengue cases in African countries increased by 140%, from 48,800 in 2023 to over 118,000 by October 2024.

The map below shows where cases of dengue fever were reported in African countries in 2023 and 2024. Ethiopia had the misfortune of experiencing two dengue outbreaks in the past two years.

No dengue fever cases have been reported in South Africa but, says the National Institute of Communicable Diseases, the type of mosquito that carries dengue fever, Aedes aegypti, is present in certain regions, such as the KwaZulu-Natal coastline.

Floods, droughts and cholera

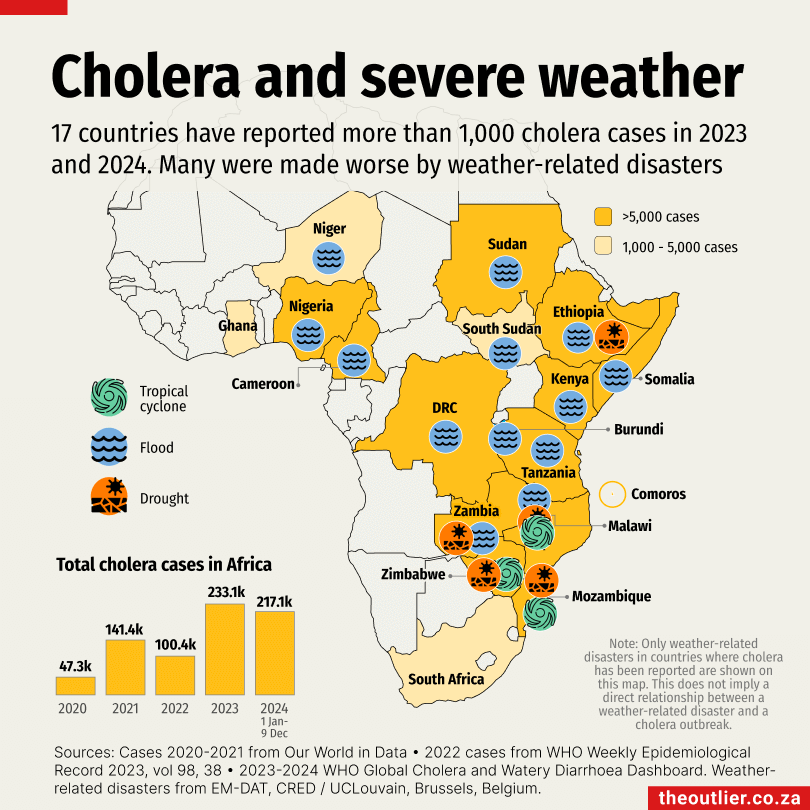

The increasing frequency of extreme or severe weather events, such as floods, cyclones, extreme temperatures and droughts damage infrastructure, contaminate drinking water sources and reduce access to clean water, creating an ideal environment for cholera to thrive.

Seventeen African countries reported more than 1,000 cases each of cholera in 2023 and 2024. Many of these cholera outbreaks were linked to or made worse by weather-related disasters. The map below shows those countries as well as weather-related disasters reported over the same period in the EM-DAT international disaster database.

Malawi, for example, experienced its biggest cholera outbreak ever thanks to flooding caused by two tropical cyclones in early 2022. Then in March 2023, Cyclone Freddy, hit. The cholera health emergency lasted from December 2022 until July 2024. In 2023 and 2024 alone more than 41,000 cases of cholera were recorded in Malawi by the WHO and more than 1,000 people died.

Cyclones and heavy rains also intensified a cholera outbreak in Mozambique, and epidemics in Zambia and Zimbabwe were exacerbated by both drought and floods.

South Africa’s cholera outbreak in 2023 was not weather-related, but started when an infected person travelled from Malawi to Gauteng. Similarly, an outbreak in the Comoros this year has been linked to a passenger who arrived on a boat in January.

Migration

Changing rainfall patterns such as severe drought can push people to migrate away from affected areas, as can conflict.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo conflict and floods has forced people to move to camps where conditions are crowded and access to clean water is limited. In Ethiopia, Sudan and Somalia, the internal displacement of people worsens cholera outbreaks.

In Sudan, conflict since April 2023 has caused the displacement of 10-million people. Here too floods have worsened the situation.

Poverty, malnutrition, poor sanitation, lack of access to clean drinking water and poor access to health care are exacerbated by changing climate patterns.

There is a need for infrastructure that can withstand extreme weather and ensure medical supplies during crises, states the Climate Change and Epidemics Report. Countries need to build systems to ensure communities are able to adapt to changing conditions and are less vulnerable to disease outbreaks.

Dilemma of South Africa’s $13.8bn climate financing deal

Many wealthy countries, and some in the Global South, are already relatively far along in their shifts to cleaner energy. Some emerging markets, however, are falling behind, partly because they do not have the funding required to scale up their clean energy industries.

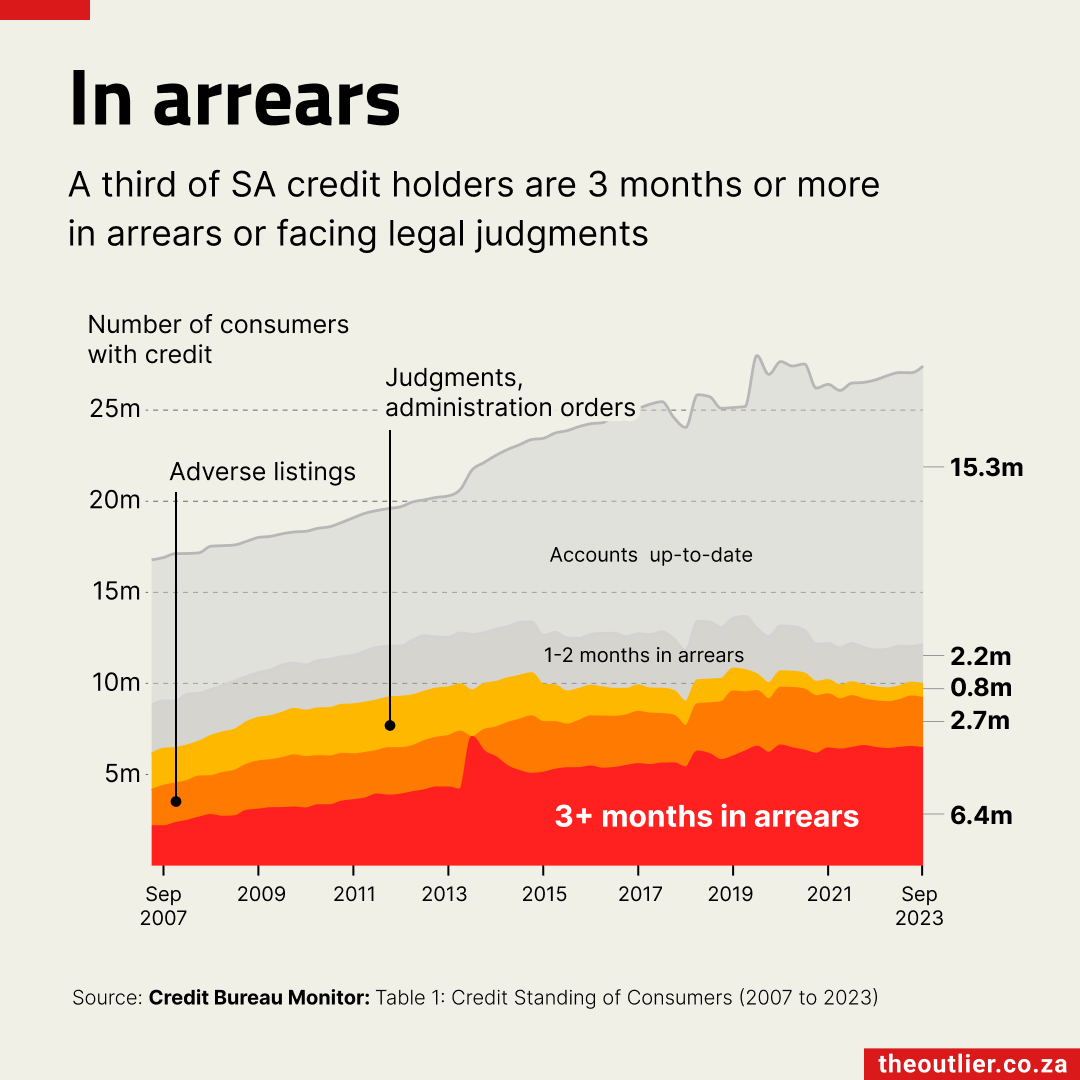

In this context, South Africa was an obvious candidate for a major climate finance deal. As coal accounts for more than 80% of the nation’s electricity mix, the country ranks among the 15 largest emitters of greenhouse gases from fossil fuels.

In 2021, at COP26 in Glasgow, the International Partners Group (France, Germany, the UK, the US and the European Union, along with Denmark and the Netherlands) pledged $8.97-billion to help South Africa decarbonise its economy, a figure that has since increased to $13.8-billion.

Concessional loans make up $7.6-billion of this funding, which is more than half of the total amount. Concessional loans are loans offered on more favourable terms, such as reduced interest rates, but still require repayment.

Although concessional loans can reduce borrowing costs for South Africa, critics argue they still place a financial burden on the Global South, which is already disproportionately affected by climate adaption and socioeconomic challenges.

Grants make up 7% ($820-million) of the pledged funding. The presidency’s grant register breaks down $613-million of that funding into 152 projects, of which 48 are completed and 87 are at the implementation phase.

🔗 Special feature: South Africa’s Road to a Just Energy Transition

South Africa’s energy shift: How the just transition is shaping the future

As the world races to embrace new technologies to avert climate disaster, South Africa is rolling out a plan to ensure its energy transition doesn’t leave communities or workers behind.

With global goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 45% by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050, scaling up clean energy sectors has become increasingly urgent. For South Africa, where coal powers more than 80% of the electricity mix, this transition will be challenging.

Our latest in-depth and interactive feature explores how South Africa is navigating this challenge and examines the social and economic impacts on coal-reliant communities.

👁 EXPLORE: The Road to a Just Energy Transition

with The Outlier

• Getting started with spreadsheets

• Learn pivot tables

• Data visualisation tips

• Map-making with data.

Plastic waste in Africa set to quadruple by 2060

The amount of plastic waste in Sub-Saharan Africa will quadruple by 2060. The region will be one of the world’s biggest sources of plastic pollution in rivers, lakes and oceans, according to projections by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

In 2019, 22-million tonnes of plastic, most of it mismanaged waste, made its way into rivers and oceans. Worldwide plastic use will triple in the next 40 years. It will increase the most in developing countries in Asia and Africa.

South Africa, Egypt and Nigeria are the three biggest contributors to plastic pollution in Africa. In 2018, South Africa ‘leaked’ about 107,000 tonnes of plastic into water ecosystems, according to a study by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

In 2022, 175 countries voted to create a treaty to eliminate plastic pollution. In November 2024, governments will come together in Busan, Republic of Korea, for the fifth and last round of negotiations for a global treaty to end plastic pollution.

🔗 This was first published on 5 December 2023. For more like this, browse the full Our World in Charts collection

July rainfall breaks weather records in Western Cape

A series of cold fronts brought severe weather and record-breaking rainfall to the winelands and Cape Town in July, with at least 12 weather stations reporting more than 300mm of rain, according to data from the South African Weather Service.

Most of the rain fell in towns along the mountain ranges of the Boland and the Hottentots Holland. Franschhoek received 619.2mm, making it the town’s wettest month on record.

Kenilworth race course in Cape Town recorded 563.2mm, the second-highest amount in the province. In Newlands, 5km away, Kirstenbosch national botanical gardens recorded its wettest month since 1999 with more than 500mm of rain.

July’s rainfall is the highest recorded in Cape Town for the month in the past 60 years, says Prof Guy Midgley from Stellenbosch University’s School for Climate Studies. This is despite a drier-than-normal start to the winter.

Based on records dating back to 1901, the Western Cape typically receives an average of 41mm of rain in July.